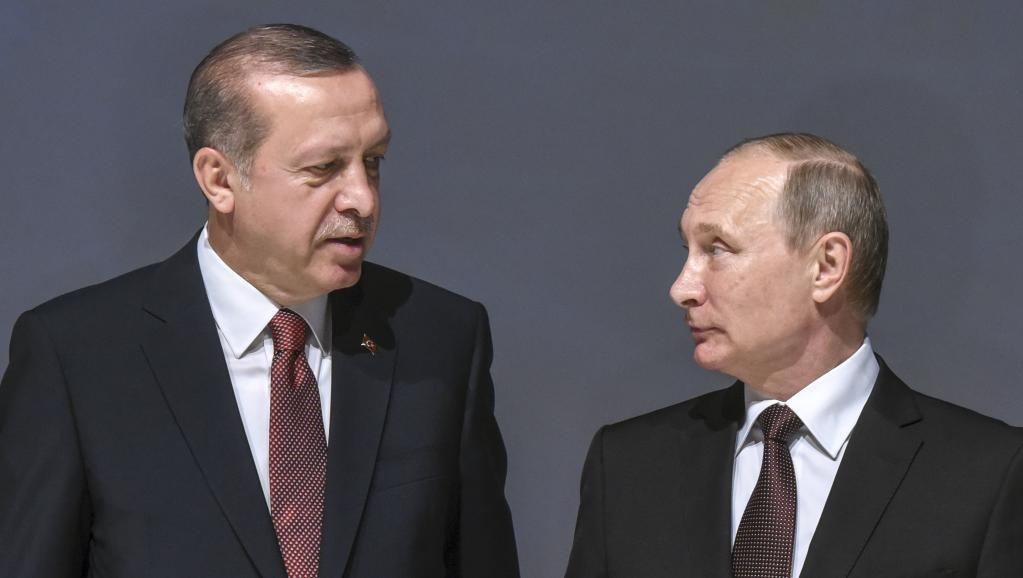

Turkey and Russia are unlikely allies, having waged wars for the better part of their history, it is a rare sight to see the two powers fraternising. The year 2015 has foreshadowed no different, first Turkey shot down a Russian warplane and then Russian Ambassador Andrei Karlov was assassinated in Ankara less than a year later. Although this historic low point in the relationship passed with no direct confrontation we can only see very limited cooperation in its aftermath.

It is the intention of this policy observer to introduce three further factors that contribute to the worsening of Russo-Turkish relations in 2021.

Fading ‘Energy diplomacy’

In reviewing Russian foreign relations, it is customary to begin with the energy sector, as if Gazprom and Rosatom were premier departments of the Foreign Ministry. In the case of the Moscow-Ankara axis, two key projects constitute this relationship: the TurkStream gas pipeline and the Akkuyu nuclear power plant.

While its construction began in 2017, when Russia supplied 52% of the natural gas imports of Turkey, the TurkStream pipeline was commissioned only in 2020, by which point Gazprom’s share in the Turkish gas imports has dropped below 33%. There are two distinct reasons for this loss in market share; the Turkish commitment to the diversification of the energy imports - mainly in the form of purchasing more Azerbaijani gas - and Erdogan’s decision to revitalize domestic production - relying on natural gas resources from fields below the Black Sea and those in the contested region of Kurdistan.

With its $20 billion price tag, Turkey’s first-ever nuclear power plant in Akkuyu is a serious project carried out by Rosatom on the Mediterranean Sea coast. Albeit, in an unconventional manner, the financing of the construction falls on the Russians, the Turkish government is obliged to purchase a minimum of 70% of the plant’s future output, at a price of 12.35 cents/kWh for 15 years. This seemingly technical data point, that is the price of electricity defined in USD, is of utmost importance as the drastic depreciation of the lira since the original deal has changed the expected Turkish expenditure from 57 billion to 140 billion liras in the period of the 15 years. Critics blame Erdogan’s ruling AKP party for the gross miscalculation which was made in an exceptionally promising and yet short-living economic boom - fresh from an IMF-backed overhaul. The repercussions of such overambitious estimates are drastic and some argue that the Akkuyu nuclear power plant will only ever be a liability for the Turkish people. It is highly improbable that the nuclear plant’s construction will halt and be left unfinished, however, Ankara learned its lesson and for its planned second power plant commissioned not the Russians, but a Japanese-led consortium.

Redrawing geopolitics

The Istanbul Canal is known to be one of the most ambitious projects of president Erdogan, however this alternative entrance to the Black Sea could be a serious security concern for Russia and a breach of an international treaty.

Throughout history, several wars were fought between Russia and the Ottoman Empire over the control of the Bosporus and the Dardanelles. This contestation of the control over the ‘gates’ to the Black Sea was eventually settled in 1936 in the Montreux Convention, which limited the size, the number and the duration of stay of foreign warships - from the navies of those nations not on the shores of the Black Sea - crossing the straits.

The new Istanbul Canal project proposes a second waterway between the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara to increase the volume of trade. The problematic part of the project arises from a unilateral Turkish declaration discussing that the new waterway will not be subject to the restrictions of the Montreux Convention. In effect, this means that through the new canal, NATO could set up a fleet on the Black Sea with no limitations in size or power. Hypothetically, US Navy submarines or British aircraft carriers would patrol just miles off Russian territorial waters.

Pan-Turkism and other Neo-Ottoman ambitions in the Russian ‘near abroad’

When discussing alleged intrusions in Russian domestic affairs by foreign agents, it is always necessary to clarify what is meant by ‘domestic’. For most people and even in generic political discussions ‘domestic’ is a synonym of interior - as within one’s borders -, yet scholars of Russian foreign policy would often differ and introduce a special sphere of Russian domestic affairs that lies not within the Federation, but in its ‘near abroad’. The ‘near abroad’ is not just a sphere of influence, it is a layer of economically integrated, politically aligned and militarily reliable countries that Moscow treats as its domestic business. Prime examples of the Russian ‘near abroad’ are Belorussia and the former soviet states in Central Asia.

In light of this broader understanding of domestic affairs, it is understandable why Russian policymakers were shocked when the Turkish Defense Minister has recently visited Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. General Hulusi Akar has signed military intelligence cooperation treaties in both Nur-Sultan and Tashkent, but even more concerningly to the Russians, there were talks of a joint military exercise. While pan-Turkism is a very underdeveloped idea for an integrational block, Erdogan is dedicated to unite Turkic people. Russian security experts fear that the first step of this Neo-Ottoman ambition might be the ‘Army of Turan’, a Turkic security alliance pulling former soviet states away from ‘the mother bear’ and closer to Ankara.

A further theatre of conflict is the Southern Caucasus, where last autumn’s Second Karabakh War has proved that the presence of Russian peacekeepers is not a sufficient condition for establishing Moscow’s hegemony over a region that is heavily influenced by Turkey. Nevertheless, the conflict in the Nagorno-Karabakh region can serve as a reminder that even with each supporting opposing sides, Putin and Erdogan can cooperate and terminate a war on short notice if national interests require.

21.05.2021. Bálint Pongrácz

Download the full paper in PDF.

Images: Wikipedia/Flickr